<< Back to Lion December 2020 homepage

Archives

People just like us

We have adapted, this year, to rapidly changing circumstances, as people just like us have done before, as Margot Vaughan explains.

We see the signs and symbols of the past everyday: in plaques on the walls and gardens, in names like Corrigan House and Oscar House, the Drennen Centre and the Prest Room, the Kroger Front Turf and Jean James Oval. These signs and symbols celebrate those in our past who have risen to meet the challenges we have faced.

The past nevertheless has a habit of blending such things into the everyday, the Monash Freeway becomes merely a major arterial, William Barak Bridge just a way to get to the MCG, the Wesley blazer pocket simply a picture of a golden lion, as though the things we celebrate belong to another time, not ourselves. Yet our experience of the 2020 pandemic is a reminder that those we honour were people just like us, and past students named on honour rolls wore the same lion on their blazer, heraldic symbol of courage and strength.

Fast forward 75 years, and we might find members of the Wesley community listening to ancient recordings by the Wilkie Orchestra of ‘Wesley now and always’ or watching a lesson about fractions – using chocolate. Likewise today, if we cast our mind back 75 years we can see how others at Wesley adapted to rapidly changing circumstances.

The year of COVID-19 is also the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. It began, for Australia, on 3 September 1939, when Prime Minister Robert Menzies (OW1912) in a radio address asked Australians to steel themselves for war. ‘In the bitter months that have come,’ he said, ‘calmness, resoluteness, confidence and hard work will be required as never before.’ He could have been referring to 2020.

The Army had completely dug up the Back Turf!

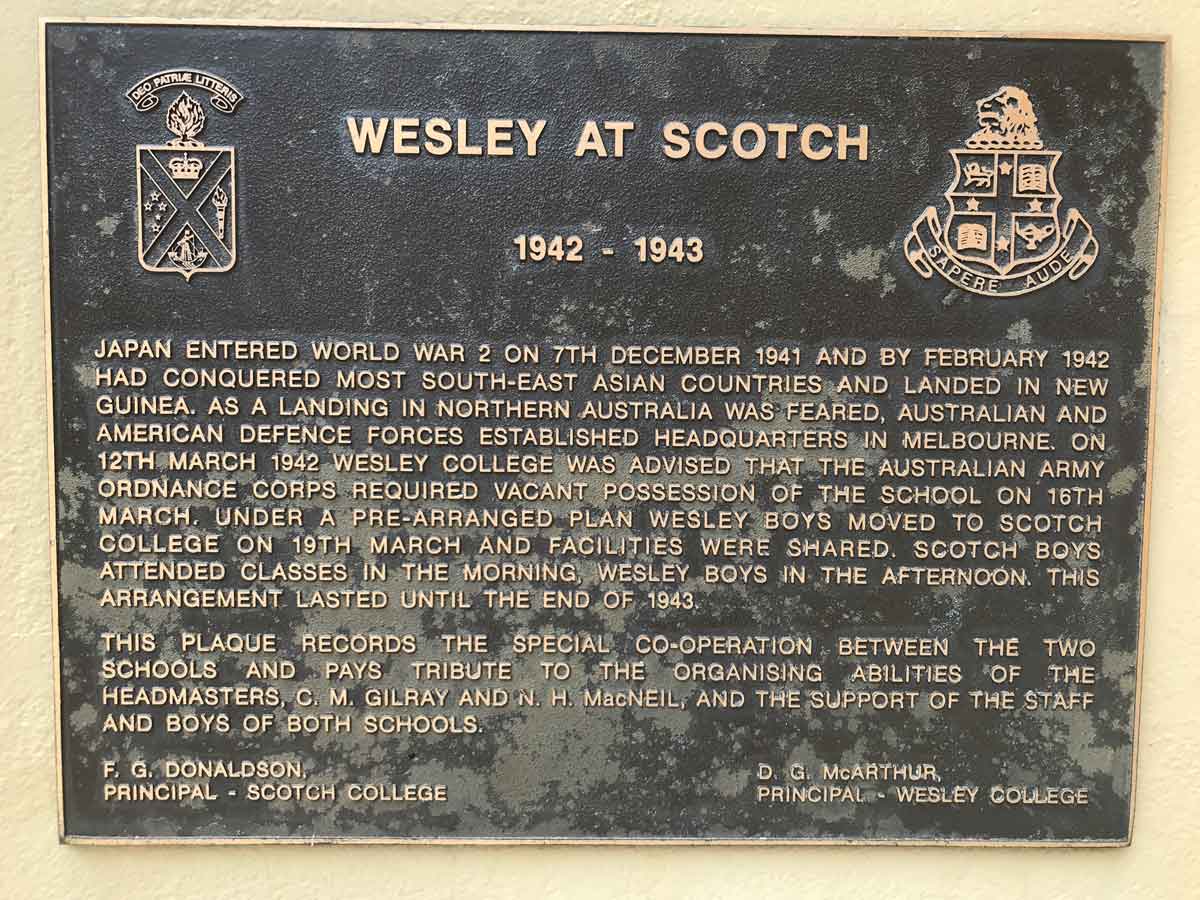

An industrial war, as Menzies noted, depended on service personnel but also logisticians and workers – two thirds of Australia’s workforce. In support of that industrial effort, the Army requisitioned the PM’s alma mater for Allied Land Headquarters. The school had to be relocated – in three weeks – but where to go? Scotch College generously welcomed students and staff, and to this day there is a special bond between the two schools, commemorated by a plaque near the Principal’s office. When students and staff returned in 1944 they found the buildings and grounds in need of much care. The Army had completely dug up the Back Turf!

Of those who served, not all came back

Many staff felt a duty to enlist, and not all survived. Bruce Dowding, a teacher and Old Collegians footballer and cricketer, was on a teaching exchange in France and joined the Royal Army Service Corps where his fluency in French was an asset. Captured in 1940, he escaped a German prisoner-of-war camp and worked for the French Underground. Sadly, he was betrayed by a fellow French Underground member, Paul Cole, and executed in 1941.

One of many other teachers to enlist was Jack Kroger. He was a junior master in the 1930s when two new students, Werner Wildermuth (OW1937) and Harold Robins (OW1938), arrived from Germany with their parents. By the time war broke out, both had graduated. Wildermuth, at university in Germany, was due to return to Australia in September 1939 but bad timing meant he was conscripted into of the German Army. Never trusted to really do his job as a paratrooper, he ‘got himself caught’ by the Allies.

Robins, meanwhile, had completed officer training at Duntroon and was deployed to the Middle East where, serendipitously, Kroger caught up with him for a few brief minutes at a railway siding, not long before Kroger’s capture by Axis forces. Escaping in Italy, Kroger made his way to Switzerland. In transit through the Suez Canal on his way home after the war, he stopped at an Allied prisoner-of-war camp in which Wildermuth was still incarcerated, but neither knew the other was there. Kroger remained in contact with both his former students after the war.

Another young teacher was Ian McBride (OW1935), a major on Ambon in Indonesia when Allied forces were defeated by the Japanese, a battle followed by terrible Japanese war crimes. McBride escaped and sailed to Australia in an open boat, navigating 1,500 nautical miles with the aid of a map torn from a school atlas. Bravely, McBride returned to active service – and survived the war.

Tim Mak (OW1940) was one of many civilians imprisoned in a Japanese labour camp near Rabaul in Papua New Guinea when Australian forces evacuated.

As Mak explained to SBS journalist Stefan Armbruster in September, ‘We are left behind, because at that time Australia doesn’t want Asians.’ Working on the docks, he supplied military intelligence to the Allies from a network of local coast-watchers.

Looking after mates

When Australian forces returned in 1945 they were looking for interpreters.

‘I said, “What sort interpreter?”’ Mak told Armbruster. ‘And they just said, “Get in the car.”’

When PM Menzies visited Rabaul in 1954, the two OWs met. ‘I introduced myself: “My name is Mak,” and he said, “Stop, stop. Where did you learn your English?”’ Mak told Armbruster.

‘”Wesley College in Melbourne.”’ Menzies replied, ‘“That’s where I went to school.” He called his number two and said, “Look after him, he’s one of my mates.”’

In that spirit, the College welcomed several refugees on staff. Dr Jacques Steininger was one: the Jewish refugee from Austria taught at Wesley for more than 25 years.

Dr Ruth Blatt (née Koplowitz) was another, on staff at MLC Cato, now our Elsternwick Campus. Anna Funder in All That I Am drew on her experiences as an anti-Nazi activist who was betrayed and imprisoned, before arriving in post-war Melbourne.

Life at Wesley during war time was undoubtedly difficult. More than 139 students and staff were killed. Australia, with a population of seven million, was feeding an extra one million Allied troops. Food, coal, petrol and even wedding dresses were rationed. We have experienced perhaps the worst social and economic upheaval since then, but just as we rebuilt then we can rebuild today for a better tomorrow. As Menzies assured Australians then, ‘You will show that Australia is ready to see it through.’

Margot Vaughan is Associate Curator, College Archives.