<< Back to Lion August 2020

The many benefits of the performing arts

Art and language have evolved hand in hand for at least 40,000 years. They are central to our humanity and an essential part of schooling if we want our students not only to survive but thrive in our rapidly changing world. Alexandra Cameron reports.

Art, like language, is fundamental to the way we express ourselves – and has been for thousands of years. According to research by Cora Lesure and Shigeru Miyagawa, linguists at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Vitor Nobrega, a linguist at the University of São Paulo, cave art evidence indicates that art may have emerged as humans began converting language and acoustic sounds into drawings.

The research suggests that cave art is often located in acoustic ‘hot spots’ where sound echoes strongly, and the fact that early artists went to the trouble of making their work in deeper, harder-to-access parts of caves suggests the acoustics was a principal reason for doing so. The art they created, in turn, may represent the sounds that early humans generated in those spots. ‘Our research suggests that the cognitive mechanisms necessary for the development of cave and rock art are likely to be analogous to those employed in the expression of the symbolic thinking required for language,’ says Lesure.

The combination of sounds and images characterises all human language, along with its symbolic aspect and its ability to generate infinite new sentences, Miyagawa notes. ‘Cave art was part of the package deal in terms of how homo sapiens came to have this very high-level cognitive processing,’ he says.

Remote rehearsals

A remote rehearsal of the St Kilda Road Senior School 'Blood Brothers' play

Elsternwick's Celebration of the Arts

On stage at Elsternwick's Celebration of the Arts

Students dance on stage at the Celebration of the Arts event

Dylan Quick plays The Last Post

Dylan Quick played The Last Post outside his home on Anzac Day in 2020

Willoughby Mims

Year 9 student Willoughby Mims plays The last post

The arts: a safe haven in our rapidly changing world

Fast forward 40,000 years, since the first known forms of cave art, to today’s rapidly changing world and it’s clear that the arts in all their variety have never been more important. The pressures on our students are on the rise. They live in an environment of volatility, confronted by everything from terrorism to bushfire crises to global pandemics. Add social media, where the absence of ‘likes’ can quickly turn an innocuous positive into a catastrophic negative, and the relentless acceleration of our technology-driven society and the need for an immediate response, and it’s no surprise that researchers currently report increasing diagnoses of youth anxiety.

Exposed to such pressures, the arts offer students a safe haven in which to consider, reflect, learn and create. Through study and performance, our students explore great themes and ideas, discover their own voice, grow in confidence and develop empathy and insight into the pressures they face.

When we come together to create music in an ensemble, say, or choreograph a dance or rehearse a play or paint a mural, we are involving ourselves in a social contract, something that extends our understanding of humanity. For example, why do we sing? Perhaps the most fundamental answer is because it is a natural thing to do. As individuals, we all have our own unique special sound; for some it can lead to a career as a soloist. For many millions, it can lead to choral rehearsals, culminating in the opportunity to share one’s voice, along with friends, at a performance in a concert hall, cathedral, eisteddfod, town hall or school hall, or even in a nursing home. Whatever the occasion, we are part of a like-minded group, sharing our love of music and of singing.

Paul McCartney once said, ‘I love to hear a choir. I love the humanity… to see the faces of real people devoting themselves to a piece of music. I like the teamwork. It makes me feel optimistic about the human race, when I see them cooperating like that.’

The arts, academic achievement and personal wellbeing

A study by Andrew Martin and colleagues from the University of Sydney's Faculty of Education and Social Work and the Australian Council for the Arts found that students who are involved in the arts have higher school motivation, engagement in class, self-esteem and life satisfaction. According to lead author, Andrew Martin, ‘The study shows that school participation in the arts can have positive effects on diverse aspects of students’ lives.’

As co-author Michael Anderson notes, ‘This study provides new and compelling evidence that the arts should be central to schooling and not left on the fringes.’

Studying a performing arts subject helps students to develop a sense of personal identity and offers a chance to belong to a group other than their regular circle of friends. For students who are not natural sportspeople, the performing arts are a great alternative to develop that sense of camaraderie with others.

It’s widely accepted that the performing arts foster self-efficacy and reduces self-handicapping as students build confidence and self-assurance. Every performer goes on stage knowing the very real risk of making an embarrassing mistake in front of their audience. Being able to get through these mistakes, which are inevitable, builds resilience and confidence in students. These are important skills for our modern society. Also, studying a performing arts subject usually includes regular rehearsal or practising. This regular practice routine develops good discipline and an understanding of the value of commitment. The long-term benefit of rehearsal is to reinforce positive work habits that are applicable to all areas of life, prompted by the short-term rewards that come from such commitment – like a great music examination result or the awe and admiration of peers after a performance.

The MIT research on language and cave art has, as you might expect, engendered plenty of debate among archaeologists, anthropologists and linguists – the types of art figures found in caves are also found outside caves, some note, and cave art may have been less about communication than about the decoration of ceremonial places. Whatever the truth, it’s clear that art and language was and still is about ceremony and storytelling, and that hasn’t changed in 40,000 years.

Alexandra Cameron is the Head of Music at Wesley’s Elsternwick Campus.

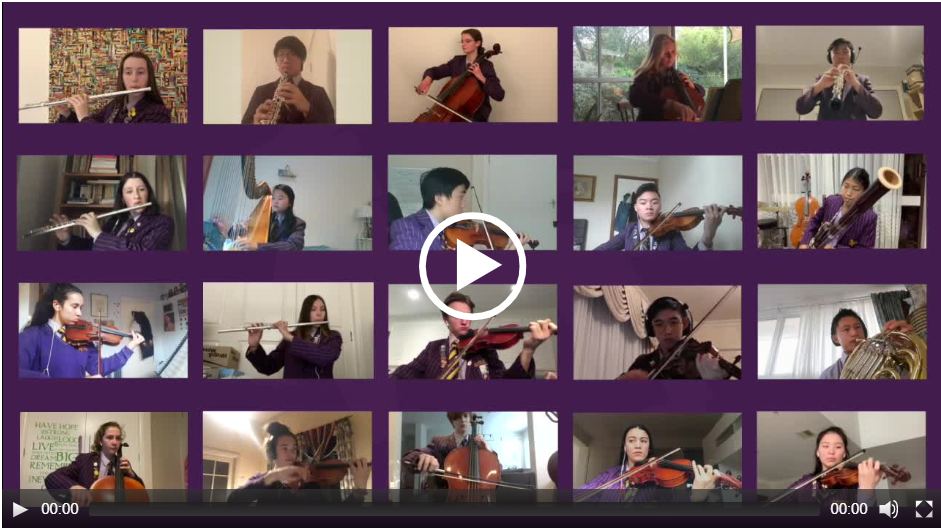

Virtual rehearsals and concerts across the campuses enabled students to engage with the arts while they studied remotely in Terms 2 and 3. The Music Schools have been reviewing ways to blend face-to-face on-campus programs and digital and virtual programs to enable students’ music making and learning, anywhere, anytime.

Music learning, anywhere, anytime

Students and teachers learned much in the virtual classroom environment in recent months, not least that a blended approach of on-campus and online learning offers the best of both worlds, as Denton Thomas explains.

It’s late one night and the Heads of Music and key Music School staff across Wesley’s three metropolitan campuses are reconvening with colleagues from the Wesley College Institute. We’re meeting to refine our planning for the delivery of digital and virtual learning tasks, following a review of our core curriculum and digital tools that best enable us to deliver it. If you think the timing is March 2020, campuses are about to be closed and we’re planning for teaching in virtual classrooms, think again. It’s 2018 and we’re building our online teaching and learning program with the support of colleagues in the Institute and IT.

Evolution not revolution

The fact is, music making and music learning across Wesley’s Music Schools has involved a blend of face-to-face on-campus and digital and virtual programs for some time. So when temporary campus closures to contain the spread of COVID-19 were announced in March, we were well placed to deliver online music learning, based on a strategy that had long been in development and using programs and platforms with which students were already familiar.

Our online music program for students at home didn’t require a complete re-design because we had already planned digital and virtual learning tasks that, in most cases, fitted nicely into the College-wide remote learning program. Sure, there were adaptations that we had to make, but music classes essentially continued along their planned pathways – without rewriting the core curriculum – and collaboration between Music School staff looked a bit different than it had.

Blended learning

The evolution of our music programs to incorporate digital and virtual approaches was driven by our desire to align courses and the units and tasks within them across year levels and campuses. Campus closures in response to the pandemic have actually been helpful in this regard as the urgency of the situation demanded quicker decision-making. Sure, there was still plenty of work to be done, but the music planning and program delivery we already had in place made the job that little bit easier.

Our planning and existing program delivery also had an added benefit: because our rollout of digital and virtual programs had essentially been incremental – albeit accelerated as we prepared for learning at home – we were well-placed to think through our medium- to long-term planning and how best to deliver the music curriculum into the future, through a blend of on-campus and online learning, once students were back on-site.

‘War room’ planning

Back in 2018, our ‘war room’ planning identified some key principles to guide curriculum delivery, whether on-campus or online. Firstly, we wanted to ensure the curriculum guided the delivery, not the other way around. Second, we wanted to use on-campus or online approaches that were appropriate and enabled authentic learning. Third, we wanted to select software and develop approaches that were efficient. This third principle guided us to identify approaches to teaching and learning that were re-usable and could be optimised and repeated with different year levels, and that were permanent or at least long-lasting solutions.

We also wanted to be able to standardise our documentation and processes, and our communications with students, and we wanted to prioritise digital approaches to designing, teaching and the administration of courses that reduced paper-handling, double-handling, supported agile design and iteration, and made our resources, course information and other data available within and across our Music Schools.

With good planning, careful thought about when and how we blend on-campus and online learning, and a little hard work, we’re enabling our students’ music making and learning, anywhere, anytime.

Dr Denton Thomas is a teacher in the Music School and Head of Brass at Wesley’s Glen Waverley Campus.